Kanaky / New Caledonia in Context: French Imperialism versus a Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific

The Pacific nation of Kanaky (known by its colonial name New Caledonia) has been in the news recently due to the outbreak of riots and unrest. While Kanaky is still in the news I would like to situate the current moment in a broader context. There are three aspects of that context I’ll discuss. The first is the history of colonisation and resistance to it in Kanaky itself. Secondly, that of the long struggle for a Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific, and thirdly of a larger struggle against French colonialism.

What is happening?

Riots began in Noumea on the 13th of May, and quickly spread and escalated. Rioters formed barricades and cut off access to the airport. In Aotearoa our mainstream news coverage initially focused on what an inconvenience this was for the handful of NZ citizens who happen to be there and want to leave. The NZDF has cooperated with the French to organise evacuation flights for New Zealanders. There has been some good interviews such as this article by Rob Campbell, and this one that quotes Kanaky leader Jimmy Naouna, which gave us an Indigenous perspective and emphasised that these riots are not happening in a vacuum but are the result of French reneging on the commitments of the Noumea Accords.

The French response has been intransigent, they declared an emergency, banned TikTok, and increased the police presence to 3500 to bolster their forces on the island. French president Macron’s early rhetoric was that order must be re-established “at any cost”, However when he visited the island on the 22nd of May he indicated that the proposed electoral changes that sparked the insurrection would be held off for the time being.

Since then the unrest has gradually subsided. Most foreign nationals and tourists have left the island, and the state of emergency was lifted on the 28th of May. Tensions remain high, and other than police both independentists and loyalists have formed armed militias. It remains to be seen what lasting outcomes there will be.

Image from this article https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2024/04/20/ytow-a20.html credited to the CCAT

The Independence Struggle in Kanaky

The immediate trigger of the riots was the French parliament passing a law to give voting rights to settlers that have arrived since 1998, and resided in Kanaky for ten years or more. This undermines the ability of the indigenous Kanak people to have self determination through democracy as they now make up just 40% of the population. It also goes against the Noumea Accords, a 1998 peace agreement between France and the independence movement that was supposed to give autonomy and create a process for eventual independence. It was always flawed and tilted in favour of the status quo however.

The accords allowed for a series of three referendums on independence, which took place in 2018, 2020 and 2021. Importantly, only those eligible to vote at the time of the accords in 1998 and their descendants would be eligible to vote in future referendums. This was so that France couldn’t use continued arrivals of French settlers to influence the result of the referendums. This rule excludes about 42,000 people from voting. This is out of a total population of about 300,000, and is mostly people of French origin or from other French colonies in the pacific.

In the first of these referenda 57% voted against independence, in 2020 that dropped to 53%, the 2021 referendum was hugely controversial as it took place during covid disruptions and the pro-independence side had sought to postpone the referendum to its originally scheduled 2022 date. The French authorities pushed ahead regardless, so the independence side boycotted it, resulting in a 96.5% against independence result but just 43.87% of eligible voters participating.

The French have treated this as a legitimate victory, while the independence movement rejects the result. This has created a situation where the French want to see the independence question as now closed, while the Independence movement views that they’ve been cheated out of a possible victory. It's in this context that the enfranchisement of French settlers post 1998 seems to be an attempt by France to put self determination forever off the table for the Kanak people.

The Kanak people have been fighting for their independence for 150 years. In the early 1800’s French and Australian traders engaged in the practice of ‘’blackbirding’. Blackbirding was a dark and not well acknowledged chapter in Pacific history, that was essentially a slave trade to get labour for sugar plantations in Queensland and Fiji. The French formally annexed ‘New Caledonia’ in 1853. They used it as a penal colony, and from 1864 began mining the huge Nickel reserves on the island. The Kanaks were excluded from the French agricultural and mining economy and pushed onto reservations. There were major uprisings in 1878, 1917 and then again from the late 1970’s through the 1980s. These led to some French concessions, including a partial share in the Nickel industry, and ultimately to the 1998 Noumea accords. But despite those, the Kanak people have remained poor and marginalised in their own land.

The struggle for a Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific

Just last month some friends and I watched this documentary (A Nuclear Free Pacific (Niuklia Fri Pasifik) | Film | NZ On Screen) about the nuclear free Pacific movement. It follows the growth of the movement over the 70’s and 80’s, culminating in a series of summits of the South Pacific Forum (renamed to the Pacific Islands Forum in 1999) that drafted and signed the 1986 South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty (aka the Treaty of Rarotonga).

The first Nuclear Free Pacific Conference was a meeting of activists from across the Pacific held in Fiji in 1975 where they shared information about the impacts of nuclear testing and came up with a list of demands. The original list was no testing of nuclear weapons, no dumping of nuclear waste, no military bases, no visits by nuclear capable ships, no mining of nuclear materials and no nuclear reactors.

One of the key Pacific leaders in pushing for this treaty was the first President of Vanuatu, Walter Lini. Vanuatu was a colony of both Britain and France (known then as the New Hebrides) and gained its independence only in 1980. Walter Lini’s government immediately declared Vanuatu nuclear free along the lines of the original proposal. Lini’s political tradition and conception of Melanesian socialism is a significant influence on the leading pro-independence party in Kanaky, the Kanak and Socialist National Liberation Front (FLNKS).

Over the course of a decade the original demands rising from the grassroots were gradually watered down to something Australia would accept. The final agreement of the Treaty of Rarotonga banned testing, dumping and stationing of Nuclear Weapons but allowed for ship visits, and made no mention of military bases, mining nuclear materials or nuclear power. Part of Australia and New Zealand’s rationale for pushing the watered down accords was to make it acceptable to the US, but the US still refused to recognise them anyway, as did Britain. France, who was the power actively testing nuclear weapons in the Pacific at the time also refused to recognise the treaty. In the end Pacific Peoples and at least some of their governments managed to apply enough pressure to get some aspects of a nuclear ban in place, but they were ultimately limited and let down by Australia and New Zealand's unwillingness to stray too far from the position of their world power allies.

An independence activist from French Polynesia, Charlie Ching, said in response to the 1986 treaty “the only solution is to get independence for Polynesia as soon as possible, because as long as Polynesia is called French Polynesia, France will continue its nuclear tests. The sooner we have independence the sooner France and its nuclear tests will be gone.” France eventually tested its last nuclear weapons at Mururoa Atoll in 1996.

However now through the AUKUS alliance Australia has agreed that it will bring nuclear powered submarines back to Pacific waters, in alliance with the US and UK, countries that refused to recognise the Rarotonga Treaty. Meanwhile France to this day maintains its Pacific colonies. These include of course Kanaky (New Caledonia) as well as Wallis & Futuna and Tahiti (French Polynesia).

The International struggle against French colonialism

This situation is not unique to the Pacific. France has maintained varying degrees of control over much of its former empire. In the 1950s France engaged in two brutal, repressive and arguably genocidal wars against independence movements in Algeria and Vietnam. France ultimately lost these wars and lost control of its North African and South-East Asian colonies.

The French actually began nuclear testing in the Pacific only after Algerian independence meant they could no longer test there, showing the interconnectedness of these anticolonial struggles.

After those losses France no longer had the political or military will to fight independence movements, so it followed the British example by negotiating semi independence for its remaining African colonies while maintaining influence through military bases, control of currencies and preferential trade agreements.

The trade between France and its former African colonies is very uneven. As of 2016 France was importing € 1.6 billion, this was predominantly raw materials and unprocessed agricultural products, such as timber, cacao, fruit, oil and uranium. In turn these countries imported €4.4 billion, mostly pharmaceutical products, cereals, electrical equipment, machinery, vehicles and aeroplanes.

Not only does this mean France has a net gain, but this also acts as a barrier for African countries trying to develop their own manufacturing or processing, or beneficial trade networks with each other.

An uneven trade relationship

It’s worth highlighting uranium specifically. All the uranium mining in Niger is done by a French-owned company called Orano. Uranium from Niger makes up about 17% of France’s consumption. 70% of France’s electricity is produced by nuclear power. Meanwhile just 1 in 7 Nigeriens have access to electricity. So we can see how the extraction of natural resources is still benefiting France at the expense of those that should own it.

Today, France has military bases in these former colonies: Gabon, Senegal, the Ivory Coast and Djibouti, and until recently it had bases in Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso and the Central African Republic (we’ll get back to these in a moment) as well as in its Pacific, Caribbean and Indian Ocean territories.

Controlling the currency

Another pillar of French influence in Africa is the CFA Franc system. The system is complicated, but it’s essentially 3 separate currencies that have a set convertibility to the Euro. The claim France makes is that these currencies are especially stable for the nations using them, but this is dubious at best, and there are many downsides. The mechanisms of the currency make it very difficult for the users to export anything other than raw materials, or keep foreign exchange reserves. But most importantly they take away the monetary sovereignty of the African nations in question.

The combined effect of the military presence and the currency control is that France has managed to keep preferential access to the natural resources of its former colonies, and an outsize influence on their internal politics, regardless of official independence.

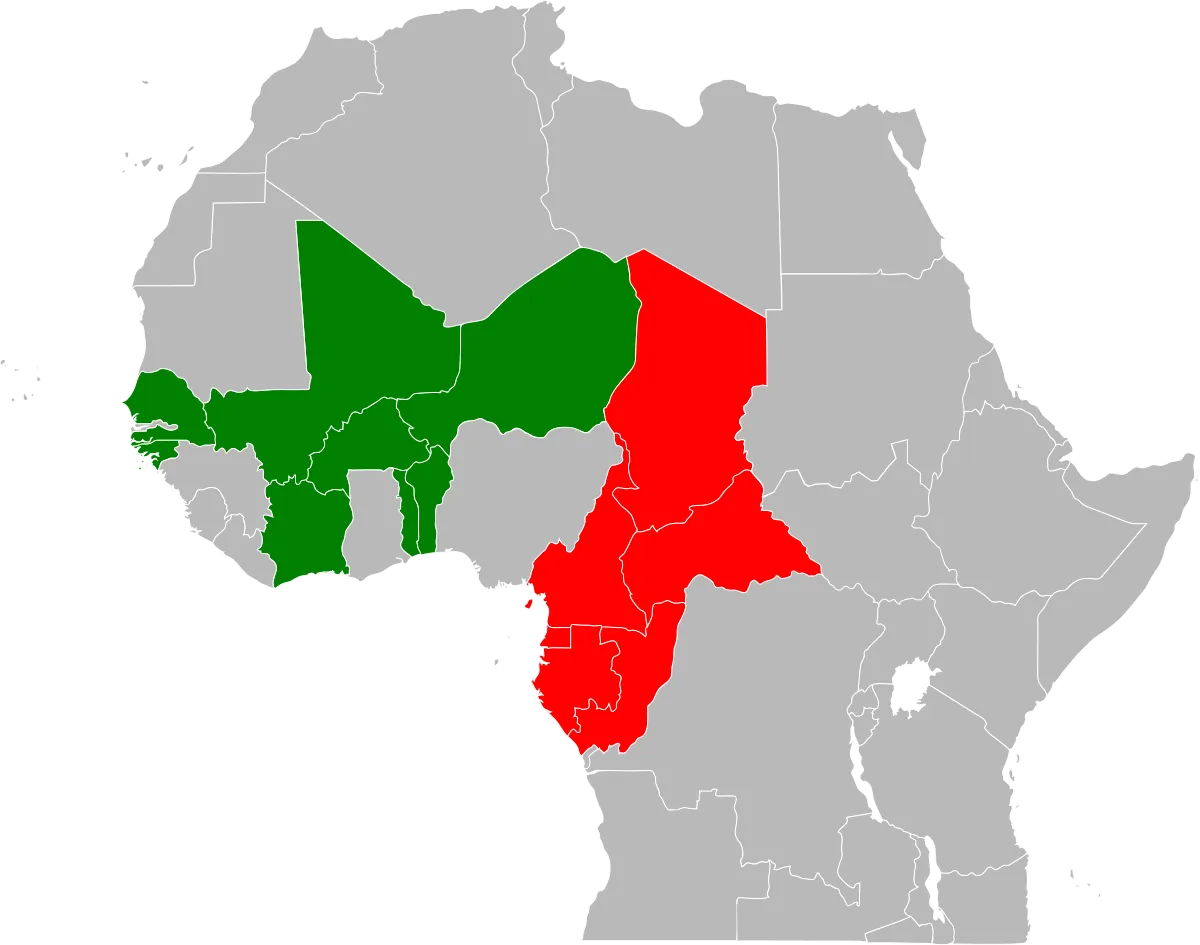

The CFA Franc zone from Wikipedia https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CFA_Franc_map.svg Countries using the West African CFA franc are green; countries using the Central African CFA franc are red.

France’s non-independent empire

But even this sham independence was only afforded to France’s larger colonies with big populations and territories it couldn't control. The rest of its empire has remained as one of a few different categories of Overseas territories. This includes Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint Martin and Saint Barthelemy in the Caribbean, St Pierre and Miquelon near Canada, French Guiana on the South American continent. There’s also Reunion and Mayotte in the Indian Ocean near Madagascar and a number of uninhabited (except for military and scientific bases) islands in the Indian Ocean and Southern Ocean, as well as of course the Pacific colonies mentioned earlier.

Cracks in the empire

This vast system is inherently unstable however. The various colonised peoples of France’s empire can't be suppressed forever, and France’s control is weakening. The CFA Franc system has gone through several restructures and is constantly being contested. Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger and Gabon have all seen French-backed leaders overthrown in the last few years. The military governments that replaced them are openly rejecting France’s influence, including closing the military bases that used to be there; some of them have been talking about leaving the CFA Franc zone.

In February last year Martinique changed its flag from a colonial era French one to one that reflects its African heritage. In June last year huge protests wracked Paris after the police shooting of an Algerian teenager; the protests spread to Martinique and Guadeloupe in the Caribbean as well as Reunion.

Coming back to the present crisis in Kanaky, the leaders of Martinique, Guadeloupe, Reunion and French Guiana have recently sent an open letter encouraging France to seek a political solution in Kanaky rather than continue repressive tactics.

Will Aotearoa sit and watch Kanaky’s fight for independence?

Back in the 1980’s the original Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific movement achieved a huge milestone by creating just the second nuclear free zone in the world. But Australia and New Zealand vacillated between siding with our Pacific neighbours and our Anglo sphere allies, and this undermined the goals of the movement.

The current riots in Kanaky are a reminder of the unfinished work of the NFIP movement and decolonisation in the pacific. Aside from Kanaky and the other French colonies there’s also American Samoa and Guam (US), Pitcairn (UK), West Papua (Indonesia) and our own relationship with Niue, Tokelau and the so-called Cook Islands that need examining.

It’s time for us to rebuild a mass movement for a Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific that learns from the efforts of the previous generation and similar struggles worldwide. This has to go hand in hand with decolonisation at home.

There is a striking similarity between the use of referendums to flout Kanak independence and the use of referendums to remove or prevent the formation of Maori Wards, or the ACT party’s proposed referendum on Te Tiriti. Settler colonialism has a funny way of twisting democracy. So this is also a reminder about the importance of constitutional transformation and the Matike Mai process to shaping a decolonised Aotearoa. French imperialism across the world is shaky and lashing out. Will we stand for the independence of our neighbours or sit and watch? Will we prop up settler colonialism or support decolonisation? Will we join AUKUS and NATO or chart our own path?

References

Campbell, R. (2024, May 20). The Unrest in New Caledonia is not caused by locals but by the French. The New Zealand Herald. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/kahu/the-unrest-in-new-caledonia-is-not-caused-by-locals-but-the-french-rob-campbell/6U73UHVQKFARNIMMSIGGFAGO2I/

Morah, M. (2024, May 20). Kanak political leader speaks on New caledonia Unrest. Newshub. Kanak political leader speaks on New Caledonia unrest | Newshub

Miller, C. (2024, May 19). New Caledonia unrest: NZDF set to bring home stranded kiwis - Peters. 1 News. New Caledonia unrest: NZDF set to bring home stranded Kiwis - Peters (1news.co.nz)

Willsher, K. (2024, May 20). New Caledonia: Macron calls further security meeting as deadly unrest grinds on. The Guardian. New Caledonia: Macron calls further security meeting as deadly unrest grinds on | New Caledonia | The Guardian

Stevens, L. (1988). A Nuclear Free Pacific (Niuklia Fri Pasifik) https://www.nzonscreen.com/title/nuclear-free-pacific-1988

Dekker, I. (2020, Feb 22). How much money does France make in French speaking Africa. Medium. How much money does France make in French-speaking Africa? | by Inemarie Dekker

Maad, A. (2023, Aug 7). How dependent is France on Niger’s Uranium. Le Monde. How dependent is France on Niger's uranium?

Faye, M. (2023, Nov 6). Why does France have military bases in Africa?. BBC.Why does France have military bases in Africa? (bbc.com)

Balima, B & Bavier, J. (2024, Feb 13). For West African juntas, CFA Franc pits sovereignty against expediency. Reuters. For West African juntas, CFA franc pits sovereignty against expediency | Reuters

Power Africa in Niger | Power Africa | U.S. Agency for International Development. n.d

Great to have this timely analysis from Jon as to what's happening in Kanaky and why the Kanaks' moves to become independent of France should matter to us in Aotearoa.

As US, Australia and UK invite NZ to join them in AUKUS's nuclear sabre-rattling in the Indo-Pacific, it's timely to remember how we in Aotearoa declared ourselves nuclear-free and independent. Arguably we have more interests in common with the people of Kanaky than with the rulers of US, UK or Australia.

Congratulations Jon. What an excellent articls!